A discussion on Comic Lettering with Lee Nordling, Al Davison, Richard Starkings, Todd Klein, Kurt Busiek, Marv Wolfman, Michael T. Gilbert, Batton Lash, Bob Ingersoll, Bill Knapp, Malcolm Bourne, Steve Leialoha, Leonard Kirk, Howard Cruse, Steven Grant & Bryan Talbot.

This conversation took place online over the course of a week on the e-mail group Panel2Panel. I’m always keen to stimulate conversations like these — any comment that sparks a consideration of the importance of good lettering, created by a professional and thoughtful letterer, raises creator’s awareness of the role of the comic book letterer.

Many writers and artists say “Yeah, Yeah, lettering is important,” but if they don’t hear the arguments for and against, they can easily dismiss it or accept bad lettering as a matter of course.

— Richard

Lee: Hildy Meznik, the editor of the Disney books at Marvel decreed that balloons could not cross panel borders. As a writer, I could deal with it… but as an editor, I like using that technique quite a bit.

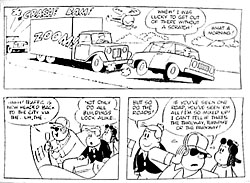

Bob: On those few occasions when I’ve done stories plot-first, I found placing balloons across panels to be an invaluable tool to make up for bad storytelling by the artist. If the artist’s layout design doesn’t tell the readers’ eyes where to go next, a balloon or sound effect which crosses the border into the next panel can move that eye to where it should go next. I always hated those little arrows that directed you to the next panel, because they made the fact that the artist hadn’t done his or her job obvious. But using word balloons or sound effects to move the eye instead of arrows is less intrusive, because it incorporates arrow’s equivalent into the actual art and story elements.

Al: Art Young, editor on the Vertigo book TAINTED that I did with Jamie Delano, wouldn’t allow captions or balloons to cross panel borders. When we asked “what, not even if it improves the flow of the page?” he just responded “it’s my ‘prejudice’ and I’m keeping it, whether it works or not!”

Marv: That’s what I like. Never let the facts interfere with opinions. BTW, I like Art – he’s a good guy. But he’s dead wrong here. Personal prejudices should not be imposed on others.

Al: Yeah I got on real well with him otherwise, good to work with… apart from that one point, nice guy… he openly admitted it was a prejudice but was determined to impose it on the books he edited.

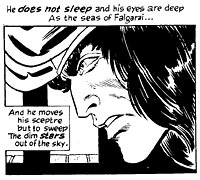

Steve Leialoha: Roy Thomas always wanted the word balloons on the panel borders whenever possible. No floating balloons. My favorite dictum of his was that Conan doesn’t think: no thought balloons for him.

Kurt: I think Roy’s definition of “whenever possible” may have been fairly loose. I just grabbed the nearest Thomas written/edited comic to hand — GIANT-SIZE SUPER-VILLAIN TEAM-UP #1, as it happens, which is about as straightforward as it gets: Roy, John Buscema, Joe Sinnott and Artie Simek — there’s a floating caption on the splash, six floating captions on the 2-3 spread, three floating balloons on p.4, another on p.5, another on p.6 … Shooter would have moved them all, plus others that touch or overlap panel borders, but nonetheless aren’t at the top or the bottom of the panel. The panels wouldn’t have looked as good, but they’d have followed his rules…

I always liked Len Wein’s dictum that he explained to me in 1983: Balloons at the top of the panel should butt to the border, if possible, balloons at the bottom of the panel should float. They’re balloons, they’re full of air, they do that! That’s the sensibility that works the best for me.

Of course, as pencillers leave less room for balloons, and as electronic lettering brings about production changes, it’s not always possible to do that — plus, when the writer rattles on enough to fill all available space, you also run out of choices.

No thought balloons for Conan was a narrative choice more than anything else. Whenever Conan’s thoughts needed to be related, they went into the narrative captions, which added to the pulp feel. There, Roy was specifically trying to evoke a tone based on a heavy prose narrative, and for the most part it worked well. Plus, he’d had those years writing the Vision, in AVENGERS, and he didn’t get thought balloons either, except for a couple of times that were apparently enough to convince him it didn’t work for the character.

Howard Cruse: It was like pulling teeth to get most (not all) of my students at the School of Visual Arts to take seriously the notion that planning ahead for balloon positioning was integral to creating a comic book page. They had all absorbed the “doing it the Marvel way” as an excuse to ignore the whole issue. Unless I nagged them relentlessly they would end up with cramped, tiny lettering squeezed awkwardly in whatever nooks and crannies were available between the expansive panoramas of swinging fists. For me, balloon placement is integral to the design process. I see no problem, however, in letting them (or elbows or sound effects, for that matter) cross panel borders and gutters. I like tying the full-page compositions together that way. Long, uninterrupted horizontal and vertical lines get monotonous fast, at least in my current aesthetic. (Which is not to say I can’t be a feverish admirer or artists who are strict about their grids, as were some of my favorite comics creators of all times like the Little Lulu team of the fifties.

I also enjoy violating strict rules of three-dimensionality that undercut any pretense that a panel is a “window” through which readers are peering. Often, for example, a balloon will be positioned “behind” a character’s head while nonetheless extending “in front” of the panel’s edge even though the character is theoretically “behind” that edge. In other words, just as the presentational theatre style, in contrast to more “realistic” styles, acknowledges and uses the fact that the actors in a make-believe world are actually in the same room as audience members who can be addressed directly when circumstances make it dramatically useful, the comics I create intentionally remind readers frequently that they are ink lines on a flat piece of paper and that the “real” action is taking place in the imaginations of those readers with the ink lines serving as a guide and stimulus.

It was a big step for me when I said good-bye to exclamations at the end of every sentence. I was increasingly aware of the syntactical absurdity of the practice early in Wendel’s six-year run, but I stuck with them throughout out of sentiment for an old comics tradition plus a disinclination to change styles in the middle of a series. With Stuck Rubber Baby I made the break.

I’m not ready to give them up with sound effects, though — especially with loud ones that are inherently sharply plosive and hence emphatic. I can’t logically defend an exclamation after a “Sniff!” I’ll admit, but even there I’m not quite ready to give ground. There are conventions in comics that have no parallel in written literature but are nonetheless expressive. I would put bold-facing as an indicator of vocal inflection (not importance of content) in that category. In a dialogue-dependent medium, having that extra tool to help indicate what an actor would do with aural inflection on the stage is not something I’m willing to sacrifice just because the tool is not used by text-only writers.

On the other hand, the notion of always boldfacing “Batman” or “Superman” regardless of inflection, as DC always used to do (I haven’t checked lately to see if the practice persists), struck me as arbitrary and stupid even when I was eight.

I think its good for all of us to use or forego specialized comics tools according to our taste and sense of what’s appropriate at a given moment in a story. To have rules like “Balloons should always be at the top” offends me as would any global proclamation about how artists should go about expressing themselves.

Steven Grant: Overuse of SFX just clutters up the page. My general rule of thumb these days is not to add SFX to actions visible on the page, since reader imagination can add sound just as well, and I doubt most readers need to know what a punch or a gunshot sounds like; I suspect most SFX along those lines actually hinder reader appreciation by limiting the “recognized sound” to what’s expressed by the SFX. On the other hand, off-panel actions often need SFX to make them understandable, particularly if characters on-panel are reacting to the sounds. (A gunshot’s a good example here as well; several characters turn apprehensively toward the sound of an off-panel gunshot.) Wherever an SFX is necessary to make the meaning apparent, it should be used. Wherever it’s redundant to the action in the panel, it should be avoided.

My other favorite use of SFX, also not to be overused, is to have dialogue as SFX erupting out of a speech balloon for effect, to add extra special emphasis.

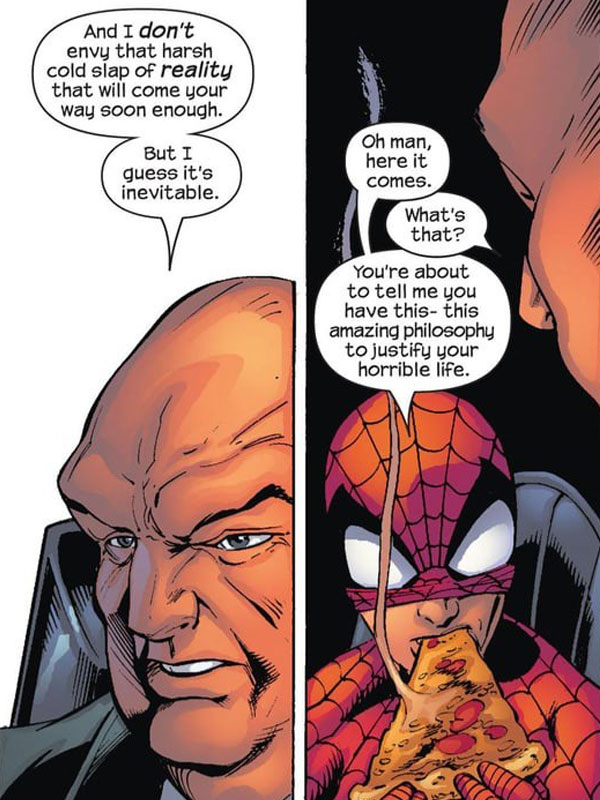

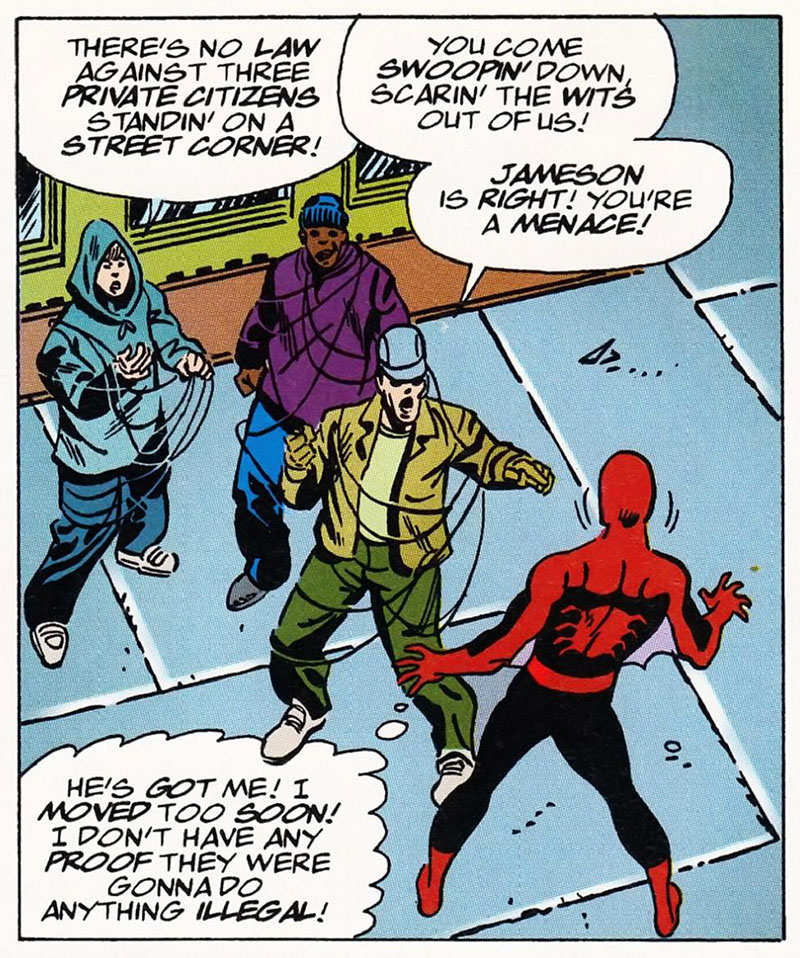

Rich: I teach students and Comicraftsmen that lettering sits on two dimensional planes — like panes of glass — which might be in front of, or behind, the speaker or speakers. We show examples of panels from SPIDER-MAN: CHAPTER ONE — written, drawn and lettered by John Byrne — that show characters breaking this 2 dimensional space. The effect, I think you’ll agree, is a flattening of the image, or, as Jim Shooter would say, the characters objectify the balloons.

Nevertheless, I’m all in favor of students considering ideas that are in opposition to my own. I’m not one for exclamation marks at the end of sound effects, but Tim Sale insists on them, and contradicts me on this in his piece in our book.

Howard: I appreciate your point of view even though I have come to a different conclusion. I haven’t seen the John Byrne panel you use as an example, but I would argue that only mediocre drawing will make a drawing flat. If another artist wants to be concerned about 3-D consistency in a 2-D medium, I can honor his or her desire to make that a point of concern, and I myself dislike visual inconsistency when it’s the result of sloppiness. But as I said to the group, I personally feel that there’s something to be gained by subtly reminding readers that we’re all in the business of suspending belief and letting ink lines on flat paper guide us into another world of the imagination where crosshatching is translated into real light and shade, magenta and yellow dots — with maybe some cyan thrown in — turn into flesh that has feelings, and motionless icons become flowing mixtures of light and sound. But I’m still evolving and may someday even be embarrassed into lettering a gun’s BANG without an exclamation point.